As promised, it’s time to unveil all this China Study business. Grab a raw, nonalcoholic drink and make yourself comfy!

Let me start by saying that this isn’t an attempt at “debunking” the China Study or discrediting T. Colin Campbell. Quite the contrary. “The China Study” book is excellent in many ways, if only to underscore the role of nutrition in health. If I ever met Mr. Campbell in person, I’d give him a jubilant high-five and thank him for fightin’ the good fight—for exposing the reality of Big Pharma, for emphasizing the lack of nutritional education most doctors receive, for censuring the use of scientific reductionism, for underlining the importance of diet in disease prevention. Campbell and I are on the same page in many ways. His scroll of accomplishments is impressive and I sincerely believe his heart is in the right place, even if I don’t agree with all of his conclusions.

My goal here is solely to look at the original China Study data and see what it says. When Campbell’s conclusions seem valid, I’ll point it out. When Campbell’s conclusions seem awry, I’ll point it out.

For anyone who hasn’t read it yet, here’s a brief rundown of Campbell’s book and the main study it’s based on. Skip this if you’re already familiar with it (or just too impatient to sit through my drivel).

What is the China Study?

The original China Project is a ginormous study chronicling the diets, lifestyles, and disease trends in 65 rural regions in China. Its data comes from two major surveys—one conducted in 1983/84 and another in 1989/90—and uses data from diet and lifestyle questionnaires, blood and urine samples, three days of diet observation, and local mortality rates for major chronic diseases.

Intrigued? You can read more about it on the Cornell University website.

The uninterpreted data was published in 1990 in a book called “Diet, Life-Style and Mortality in Rural China.” If you want to read it, you can find it at some university libraries, request it at a public library through an inter-library loan, or shell out $90 for a used copy on Amazon.

Why the China Project design is awesome:

- People in these rural Chinese counties tended to live in the same region for life, eating the same diet from birth until death—making it relatively easy to examine nutritional patterns in relation to disease.

- Different regions often had vastly different diets: Some were nearly vegan, some ate boatloads of sweet potatoes, and one county ate two pounds of dairy foods per day (Tuoli). These wide variations make it easier to see trends than if all the data points were more homogeneous.

Why the China Project design is not awesome:

- All the collected data was aggregated at the county level, so even though many thousands of people were involved in the study, we ultimately only have 65 data points to work with. That’s not a whole lot, especially considering how many variables there are.

- Although diet and some lifestyle factors were covered, the China Project didn’t capture any information on physical activity. We don’t know how exercise habits varied between regions, so we can’t determine how activity influenced the occurrence of disease.

- Most importantly: This is an epidemiological study. There aren’t control variables, and it’s impossible to draw actual conclusions from the data. All it reveals are correlations, which may or may not be influenced by additional factors.

Indeed, a golden rule of statistics is correlation doesn’t equal causation. You might see a lot of umbrellas when it rains, but that doesn’t mean umbrellas cause the rain. You might see a particular food pop up in relation to some disease, but there’s no way to tell—from the China Project alone—whether it’s a cause, a consequence, or simply there because of a third unstudied variable.

“The China Study” book is the only reason most people even realize the China Project exists. In this book, Campbell blends research he conducted on rats, aflatoxin, and casein with the results unveiled by the China Study. His ultimate message is that animal protein unequivocally causes cancer (as well as other chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes), and he claims in no uncertain terms that the China Project data supports this conviction.

Of course, “The China Study” isn’t airtight. Here’s what I take issue with:

- Campbell projects the effects of casein onto all forms of animal protein, while ignoring research to the contrary (such as the potential anti-cancer properties of whey).

- The correlation between all animal protein and disease isn’t supported by the original China Study data.

- The book focuses myopically on the effects of animal foods, while not even mentioning the (incredibly strong) associations certain vegan foods have with disease.

A quick note on stats

Not a math whiz? No problem. The stuff here should be pretty straightforward, but in case you’re rusty or simply allergic to numbers, here’s a refresher on some of the statistics terminology I’ll be using.

A positive correlation means two variables increase together and decrease together. For example, the more food Garfield scarfs down, the more Garfield weighs; the less food Garfield eats, the less Garfield weighs.

A negative correlation means one variable increases while the other decreases, and vice versa. For example, the more Garfield exercises, the less Garfield weighs; the less Garfield exercises, the more Garfield weighs.

To simplify the numbers, I’m expressing correlations in this entry (and subsequent ones) as percentages rather than decimals. That means a correlation that’s normally 0.5 will appear as 50, for instance.

Positive correlations range from 0 – 1 (or 0 – 100 as percentages), and negative correlations range from -1 – 0 (or -100 to 0 as percentages). Due to the sample size of the China Project, correlations greater than 25 or lower than -25 are the most important to look at, and correlations closer to zero aren’t worth more than a cursory glance. The higher the number is, the stronger the correlation.

A p-value indicates how sure you are that your results are accurate and not just a matter of chance. Most statisticians like to use a p-value of 0.05 or less, which means there’s only a 5 in 100 possibility that your results are merely a fluke.

Correlations marked with asterisks indicate the following p-values:

* = p<0.05 (5 in 100 chance that the correlation is accidental)

** = p<0.01 (1 in 100 chance that the correlation is accidental)

*** = p<0.001 (1 in 1000 chance that the correlation is accidental)

Last but not least…

Even though the China Project data documents them, I won’t be looking at correlations with parasite infection, diseases caused by a specific nutrient deficiency, diseases related to environmental factors (like dust disease), and mortality for people under the age of 15 (since the data is typically too sparse to form anything statistically significant, and less likely to reflect diseases caused by long-term nutrition). Mostly, this will be about various cancers and cardiovascular diseases in relation to food.

Now we’re ready to roll. If animal protein is truly a potent, universal cause of disease in humans, we should expect to see strong correlations with chronic conditions whenever meat, egg, dairy, and fish consumption rises. Luckily for us, the China Project documented each of these food types as separate variables, so we can look at each one individually.

First in line: meat.

Meat intake in rural China

From the China Project data, we can see that meat intake ranged from 0 grams per day in Jingxing to 121.1 grams per day in Tuoli, with an average of 26.4 grams for all counties.

Since epidemiological studies are a tangled mess of correlations, we ought to look at the other factors that accompany meat eating in China so we can see the full picture. Meat consumption corresponds positively with beer consumption (+25) and liquor consumption (+26), as well as milk intake (+52), intake of refined starch and sugar (+25), egg consumption (+38), and use of snuff (+55). In other words: any diseases we find associated with meat could also be related to drinking habits, snuff usage, or consumption of these other foods.

Negative correlations with meat include intake of plant protein (-36), crude fiber intake (-49), intake of other cereal grains (-38), intake of starchy tubers (-31), pipe smoking (-34), intake of salted vegetables (-26), intake of carrots (-29), and sweet potato consumption (-31). In other words: any diseases we find meat protective against could really be due to avoidance of starchy tubers and salted vegetables, a low level of plant protein intake, and so forth.

So what does the original China Study data reveal about meat and disease?

NEGATIVE CORRELATIONS (more meat = fewer of these diseases)

Liver cirrhosis: -38**

Oesophageal cancer: -29*

Myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease: -28*

Cervix cancer: -23

All cancers: -20

Penis cancer: -18

Diseases of blood and blood forming organs: -17

Neurological diseases: -13

Stroke: -12

Diabetes: -11

Lymphoma: -8

All non-cancer causes: -6

Stomach cancer: -5

Hypertensive heart disease: -4

Rheumatic heart disease: -4

Leukemia: -3

With the exception of the first three, none of these trends are “statistically significant”—meaning the correlation is too loose to mean a whole lot. We can assume everything south of myocardial infarction isn’t terribly important. Even so, meat sure doesn’t look like the cancer-causing villain we might expect from reading “The China Study”: Its intake correlates negatively with the average for all cancers, which is a fairly important indicator. And considering meat intake occurs in conjunction with a few unhealthy factors—like beer intake, snuff usage, and lowered fiber and vegetable consumption—it’s possible that meat would have even lower negative correlations with these diseases in isolation.

Perhaps more surprising, though, is that meat actually seems protective of heart attacks and coronary heart disease—at least based on the China Project data set. A correlation of -28, and statistically significant to boot. No wonder Campbell never cited China Project data in his chapter on heart disease: The trend here favors animal food consumption.

But before diving into the nearest steak for the sake of your cardiac health, remember that confounding factors might be skewing these results. Could the meat-eaters be doing something else—a mysterious, intruding variable—that lowers their incidence of heart disease? Quite possibly. The only thing we can say is that meat isn’t playing a convincing role as a cause of all vascular diseases and most cancers.

POSITIVE CORRELATIONS (more meat = more of these diseases)

Colon cancer: +20

Nasopharyngeal cancer: +19

Breast cancer: +15

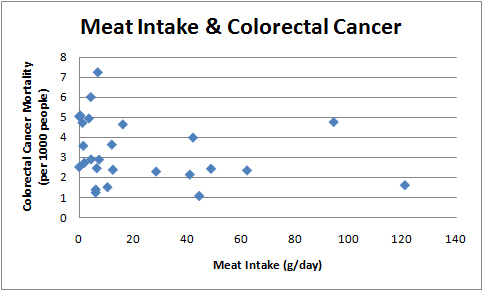

Colorectal cancer: +10

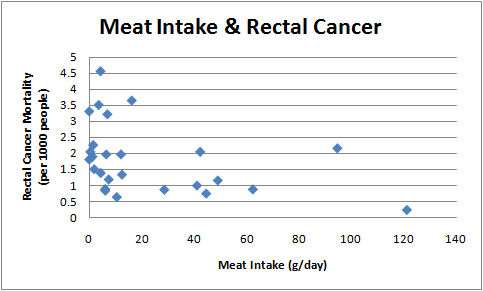

Rectal cancer: +10

Brain cancer: +10

None of these correlations are considered “statistically significant,” but let’s take a look at them anyway for the sake of illustrating variable entanglement. What we have are some diseases of the lower digestive tract, including colon and rectal. The “colorectal cancer” variable, by the way, is just a combination of the colon cancer and rectal cancer incidences in each county, although a few counties didn’t report data on these diseases separately.

The correlation between meat and these diseases isn’t alarmingly high; in fact, colon cancer has a stronger correlation with sea vegetable consumption (+56), working in industry (+41), and consuming rapeseed oil (+34). Still, the numbers are positive, and it’d be easy to take a cursory glance at this data and think, “Hey! Meat mucks up your digestive tract.”

But just for kicks, let’s look at another variable meat goes hand-in-hand with: infection with the schistosomiasis parasite. This is actually most associated with sea vegetable intake (correlation +74), but it also corresponds with meat intake because meat eaters tended to also eat more sea vegetables than average. The reason I want to look at schistosomiasis is simple: It has some crazy-high correlations with colorectal diseases.

POSITIVE CORRELATIONS (more schistosomiasis infection = more of these diseases)

Rectal cancer: +88***

Colorectal cancer: +89***

Colon cancer: +72***

Brain cancer: +36

Holy moly, right? And I came across more than a few articles like this:

Chronic infection with schistosomiasis has been clearly associated with the development of bladder cancer, and infestation is associated with a high incidence of colorectal cancer in endemic populations.

What would happen if we only looked at meat consumption and colorectal cancers in counties that weren’t infected with schistosomiasis? We’d have a clearer picture of what meat’s role in these diseases are. Time to roll up our sleeves and do some correlation-untangling!

Here are three graphs using only counties that had a 0% rate of schistosomiasis infection:

Poof! There goes any semblance of a positive correlation between meat and colorectal cancers. In fact, our new correlations are a surprising -38.5 for rectal cancer, 0.03 for colon cancer, and -24.4 for all colorectal cancers. The trend is pretty much neutral for colon cancer, but for rectal cancer, meat almost looks protective.

At any rate, it seems meat categorically evades the crimes Campbell indicts it for—heart disease, cancer, and the like—within the scope of the China Project data. A little surprising, huh?

Next up, I’ll be looking at non-meat forms of animal products: fish, eggs, and dairy. Do these suckers cause disease? Do they cure all ills? Or are they totally irrelevant in the grand scheme of things? These answers and more, coming up!

Keep up the fantastic work you do Denise! Your blog is a true treasure. Being tired of the overly euphoric and questionable preaching of the so called “raw gurus” I appreciate your realistic approach a lot. 🙂

Best wishes from Germany,

Steffi

Thank you so much for reading, Steffi! A “realistic approach” might not be as fun as the euphoric preaching, but it’s the only way to find useful answers about health, in my opinion.

Best wishes from Oregon 🙂

Denise

Denise,

What a great job in interpreting Collin’s data and making it easy for us to understand. I appreciate your unbiased interpretations and impeccable writing skills. Keep up the fantastic work you do!

I mean Campbell’s data. . .sorry.

Thank you Sue. I’ll be flooding you lovely readers with more interpretations of this data for a bit longer… let me know if it gets tedious. 🙂

Hi Denise. Well written and thoughtful article. I am not taking any chances. I eat very little chicken and fish, and no red meat. Several celebrities are eating more raw and vegan, such as Carol Alt, Ben Vereen, Woody Harrelson, and Demi Moore. I hope this way of eating catches on, as we need a healthier population in these tough times. Keep up the great work!

James Reno

Raw-Food-Repair.com

Thanks, James! I do think the raw food movement will continue to grow–especially as rising health-care costs drive people to investigate health on their own, rather than relying on doctors and drugs to treat every ailment. Knowledge is power. Thanks for visiting my blog.

Don’t be fooled people, Denise has misinterpreted raw data, just as many inexperienced “researchers” do. Denise is not qualified to read such data correctly.

Please refer to the use and misuse on pp. 54-82 of the China Project monograph.

The following is Dr Campbell’s rebuttal. The rest can be found http://www.vegsource.com/articles2/campbell_china_response.htm

” China Project results are no exception to these limitations of single experiments. It was very large, unique and comprehensive but it was observational (i.e., not interventional), simply observing things as they were at a single point in time. It provided an exceptionally large number of hypothetical associations (shown as statistically assessed correlations) that may indicate but does not prove cause and effect relationships. These unanalyzed correlations are considered raw or crude. It is highly unusual to find such ‘raw’ data in a scientific report because, in part, untrained observers may misunderstand such raw data.

For the monograph, we were somewhat uncertain whether to publish such raw data but decided to do so for two principle reasons. First, we wanted to make these data available to other researchers, while hoping that data misuse would not be a significant problem. Second, because these data were collected in rural China at a time when data reliability might have been questioned, we chose to be as transparent as possible. We discussed data use and misuse on pp. 54-82 of the China Project monograph that curiously was overlooked by Masterjohn and Jay’Y’.

John,

One, the article you linked to above was written in 2006. The article you are commenting on was written in 2010. So there is no possibility that this was a rebuttal to these arguments.

Two, I skimmed over the rebuttal and saw no effort on Dr. Campbell’s part to use any numbers, present any graphs, or provide any reasoned response to his critics. Instead, it appears that Dr. Campbell has written a quite lengthy example of the “Appeal to Authority” fallacy – the authority being himself and his history as a researcher. This is how gurus speak, by appealing to matters unrelated to the data at hand to convince one of a position. Denise has made an argument with raw, hard numbers, which should be the true measure of quality in any scientific argument.

great response. Thanks for chiming in.

John, not you again!!

John thinks science is religion.

Hi.

As you stated above that the china study didnt have any data on exercise is wrong.

There is a big section on American and Chinese caloric levels due to exercise.

She stated the study did not include data on physical activity. The average caloric expenditure for the entire population of China which you cite is not helpful in comparing outcomes across the studied population groups. Do you have evidence that the study did in fact include details of physical activity by subject or county?

fabulous post!!!!! Thanks for the hard work and research!!

“RAW MILK IS PROBABLY THE REASON” the Tuoli people are an exception to animal protein statistic claimed in Campbell’s book. He probably left it out to minimize confusion since the American people all(99%) drink junk milk.

Hey Denise! I love your blog and really appreciate your fact-based analysis. I just have a quibble with your stats 101 on p-values: “Most statisticians like to use a p-value of 0.05 or less, which means there’s only a 5 in 100 possibility that your results are merely a fluke.” That’s not quite what it means. It means that if there was no real relationship between the two variables, you would still find these results (or more extreme) 5% of the time. (see “common misconceptions”: http://www.graphpad.com/articles/pvalue.htm).

I find your critique of the study, and other stuff on your blog, to be quite valid and enlightening. I wouldn’t want anyone to discredit your data analysis skillz based on that p-value explanation. Keep up the good work! I love reading your stuff.

China study suck! If you travel to any country find like an old person and ask them what they eat? those are the one that do the same thing every day, eat the same thing every day, they never travel to any other country or eat anything different since they were a kid.

This is very interesting, You are an overly professional blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and look forward to in quest of extra of your magnificent

post. Also, I have shared your website in my social networks

Read Dr. Campbell’s response here: http://www.vegsource.com/news/2010/07/china-study-author-colin-campbell-slaps-down-critic-denise-minger.html

Hi there, just started working through your impressive work. Can you point me in the direction of the strong associations between certain vegan foods and disease?

nice

Just enjoy the food, eat all in moderation only.. life is food and food is life so do what you want and make yourself happy.

None of us are getting out of here alive.. Eat the ice cream and the chocolates..